This final blog post is a reflection of my creative reflective blog looking at methodologies. This blog post first looks at the Key Research Methods I undertook. Secondly, I looked at my research area of WOMEN IN FILM. Third, I looked at my research area of MY MAJOR PROJECT. Lastly, a conclusion of this creative reflective blog.

Throughout this past semester during the Research and Enquiry Module (and my other two practical modules on my MA Film and Television Production degree), I have been further developing my researching skills and widening my knowledge of areas in my practice of Film and Television Production. The two research areas I chose were:

- WOMEN IN FILM

- MY MAJOR PROJECT – A feature-length screenplay

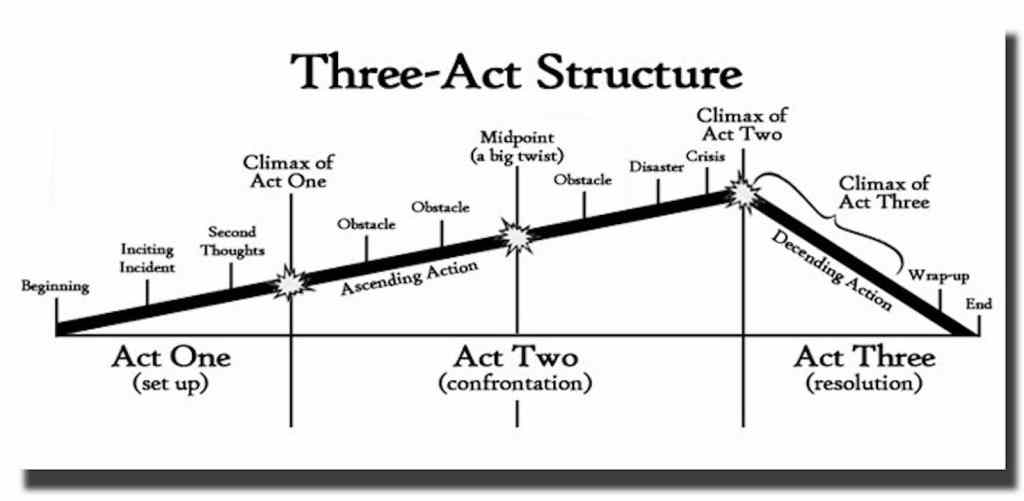

Throughout this creative reflective blog, I have not only learned a lot of new things about my practice but also a lot about myself. Partly due to this blog and the research I have undertaken, I now feel ready to start the planning stage of my MAJOR PROJECT – especially after choosing the structure discussed in my blog post Stop Procrastinating! Pick a Story Structure already!

MY KEY RESEARCH METHODS:

- Practical Filmmaking

- Pre-Production – Screenwriting

- Production – Film shoots in the Studios

- Post-Production – Editing in the Edit Suites

- Watching Film and TV

- Academic Sources

- Non-Academic Sources

- Personal Experience

- Practical Filmmaking

- Pre-Production – Screenwriting: With all the creative practices – the learning is in the doing. I have found that I have started to develop a confident writing style and this has improved due to research from writing gurus (seen in my blog post Stop Procrastinating! Pick a Story Structure already!), reading various types of Screenplays – films and television programmes alike – and then through writing which was helped by being put under pressure in the film shoot sessions on Wednesday afternoons where we had less than an hour to plan and write a one-two minute scene within my Practice 1 Module (described in my blog post Femme Fatales: “I’m Not Bad. I’m Just Drawn That Way” – Jessica Rabbit from Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988)). This key research method has helped me to be able to realise my potential as a young female screenwriter and has informed my research and my research area of MY MAJOR PROJECT – I now believe with the right amount of research (undertaken within this creative reflective blog and additional research) and practice (undertaken in my Practice 1 Module and outside of university) I now feel ready to start planning my MAJOR PROJECT – A feature-length screenplay.

- Production – Film shoots in the Studio: I have felt like the research I have undertaken for my creative reflective blog has helped me to realise the importance of theory when it comes to practical filmmaking and understanding the theory behind genres (explored in my MAJOR PROJECT research area) and the way films are made. I also believe that these practical film shoots this semester have helped inform my creative reflective blog and further research to learn about my career and myself, and also how I want to make an impact on my practice – film and television production. This key research area method although a practical one rather than a theoretical one is extremely important and has helped to inform my blog posts.

- Post-Production – Editing in the Edit Suites: Although my editing skills aren’t as proficient as my screenwriting skills, I have made sure to have a proficient knowledge of the ins and outs of video and sound editing – mostly due to the teaching during bachelor’s degree. This knowledge helps to inform my research and helps to make one a better screenwriter as I can image the ways my screenplays could be shot and edited.

These three key research areas are all practical-based methodologies rather than academic theoretical ones however as I am completing a practical Master’s degree – these practical filmmaking elements are key parts that inform my research and have helped my creative reflective posts what they are.

2. Watching Film and TV: This key research method might seem odd to most – people don’t believe me when I say I have to watch Netflix for research – but this is possibly one of the most important components as these inform my case studies. I have found in order to accurately evaluate and analyse films or television programmes I had to watch them at least TWICE!

3. Academic Sources: My favourite part of researching is when you hit the “Academic Jackpot” – as myself and my mum (who has recently completed an MSc in Healthcare Leadership) have called it – when you find a source that fits your point to a T and compliments your ideas. Throughout this creative reflective blog, I found myself using a similar method of analysing academic sources that I was taught during my bachelor’s degree which I used with my dissertation. I enjoyed going back to researching what academics thought of the topics I had chosen for my blog posts and how they were critically important to my practice.

4. Non-Academic Sources: For the cultural context for each topic, I also looked at non-academic texts like magazine articles and interviews. Although these are more subjective and not backed by academic facts it still provide appropriate insight due to the current and relevant ideas – for example, an academic book can take years to write – whereas an article can come out the day or the day after the film has released.

5. Personal Experience: This is probably the least objective as it’s coming from my own experiences but I have tried to keep an open mind when it comes to this blog and the research I have undertaken – In my creative reflective blog I have made it clear I have felt the discrimination due to my gender and this is why I chose to have the first of my two research areas to be WOMEN IN FILM. It is important to take into consideration how I as a researcher understand how my own personal experiences can help inform my ideas and make me into a better screenwriter and professional in my practice of film and television production.

RESEARCH AREA 1: WOMEN IN FILM

The main methodological approaches I took for this research area were:

- Feminist Theory

- Gender Theory

These two methodologies were crucial to my research area as it was all about gender and feminism. Within all the blog posts discussing this research area, feminism played a massive part within my ideas and reflections – gender theory was to do with the female gender. In my blog post Let’s Talk Late 20th Century Feminist Icons: Ellen Ripley and Sarah Connor, I discussed the debate of if the character of Sarah Connor was a feminist icon. I looked at both sides of the argument and the theories of Gender and Feminism helped inform the two arguments.

Individually, a few of my blog posts explored other methodologies on top of the Feminist Theory and Gender Theory such as:

- Auteur Theory: Blog Post “What does a set of ovaries have to do with directing a film?” (Jeremy Renner on Kathryn Bigelow)

- Audience and Reception Methodologies: Blog Post “Anyways, Busy Girl. Got to go.” – Lara Croft, a feminist icon

For my “What does a set of ovaries have to do with directing a film?” (Jeremy Renner on Kathryn Bigelow) blog post, the Auteur Theory helped me to explore Kathryn Bigelow’s directing style and her passion and determination to stand out amongst a male-dominated genre.

For my “Anyways, Busy Girl. Got to go.” – Lara Croft, a feminist icon blog post, the methodologies that look to Audience Reception informed my ideas that the character of Lara Croft has been sexualised by her audience since her release in 1996 and how this is still continuing on twenty-five years later.

RESEARCH AREA 2: MY MAJOR PROJECT

The main methodological approaches I took for this research area were:

- Aesthetics Theory

- Structural Theory

- Audience and Reception Methodologies

These three methodologies all helped inform my reflections into the various genres I research – action, crime, science fiction, terrorism etc.

The structural theory was most prominent in my blog post Stop Procrastinating! Pick a Story Structure already!

With all of my blog posts, an element of the Feminist theory comes through due to my personal experiences and this is mentioned in my blog post MAJOR PROJECT: Terrorism in Cinema which discusses how as a woman I have been perceived as someone who couldn’t write about such a “male-dominated” genre.

Illustrations:

Figure 1: Science Fiction Film Shoot for Practice 1 Module

My photograph